Yuji Takeoka

“everything for freedom”

Opening hours: 12:00 - 18:00

Closed on Sun., Mon., Tues., Wed. and National Holidays

Through the radical approach of transforming the pedestal itself into a sculpture, Yuji Takeoka (b. 1946, Kyoto, based in Düsseldorf) has critically explored the very framework of Western modern art as embodied by art history and museums. His meticulously selected materials, forms, and spatial arrangements, rooted in a rigorous minimalist sculptural language, not only introduce tension into the exhibition space but also create subtle openings for freeing our perceptions from ingrained conventions. Takeoka’s first solo exhibition with our gallery, everything for freedom, brings together ten sculptures and drawings, including major works from his signature “pedestal sculptures” series since 1984, along with new pieces created specifically for the unique spatial setting of SCAI PIRAMIDE.

The exhibition opens with Site Base Gold I (2024), a rectangular volume reminiscent of Donald Judd, appearing to protrude from a white wall. Depending on the viewer’s perspective, the work oscillates between two-dimensionality and three-dimensionality. While an autonomous sculpture in its own right, it subtly highlights the mechanism by which an artwork gains value when set against the gallery wall. The goldpainted surface, created especially for this exhibition, introduces an additional layer to its aesthetic structure.

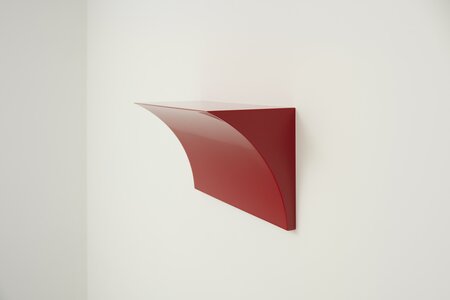

The next room features Takeoka’s early pedestal sculptures and wall sculptures. In Untitled (1984), a white pedestal placed atop a terracotta disk humorously overturns the traditional hierarchy between artwork and pedestal. Orange Pedestal (2000) accentuates the beauty of the pedestal itself through the vivid color of artificial marble Corian, while its pared-down form and artificial surface texture keep the viewer’s gaze in constant motion. In response to Carl Andre, Untitled (1989) features a single iron plate placed on the floor, enclosed within a glass case.This gesture simultaneously establishes the plate as an artwork while revealing how the absence of a pedestal allows the floor itself to functionas one, heightening the glass case’s presence as an autonomous sculptural element. Works such as Wall Pedestal (1985) and For A.P. (Andrea Palladio) (1993/2025), evocative of ornamental capitals from ancient Western architecture, similarly foreground the wall itself as a support structure through the absence of a column.

Takeoka’s awareness of spatial support extends beyond the structures and institutions of art into the realm of “living space,” as suggested in House and Garden (2007). Pedestal for Ludwig Wittgenstein (2015) draws inspiration from the exterior walls of a house designed by philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein and architect Paul Engelmann, a disciple of Adolf Loos, for Wittgenstein’s sister Margarete, a prominent socialite in Vienna. In its function as support, the pedestal and the house semantically overlap, while the absence of the supported object—or a figure of the inhabitant—redirects our consciousness toward the surrounding space.

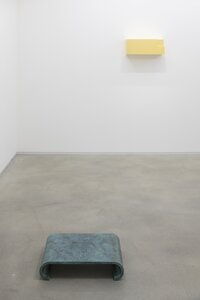

Takeoka’s methodology of “presenting space” is further evident in Bronze Pedestal (2012). However, this piece doesn’t resemble a conventional museum pedestal, but rather recalls the lacquered stands traditionally used for Buddhist implements or vases in Japanese houses. As Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917) revealed, the values of Western modern art have elevated utilitarian objects into autonomous artworks by extracting them from their everyday functional context and placing them on pedestals. Takeoka’s act of placing Bronze Pedestal directly on the gallery floor not only engages with Minimal Art’s examination of pedestals and exhibition spaces but also traces the history of Japanese ornamental objects that were prompted to evolve into modern sculpture—separating from the tokonoma alcove in Japanese style room and detaching from their display stands in pursuit of autonomy during the Meiji period. Works such as Bachi (2025), inspired by the plectrum of a shamisen, and Schatten Box Kinpaku (2006) similarly introduce Eastern forms and aesthetics into the exhibition, a deliberate gesture that merits attention.

Takeoka’s sustained questioning into the boundary between artwork (ergon) and its surroundings (parergon) (*), and his exploration of the space in-between, is deeply intertwined with his personal history. He entered art university in Kyoto in 1968, a time of fervent student movements and intellectual ferment shaped by existentialist and post-structuralist thoughts from Western Europe. In 1972, he moved to Düsseldorf, encountering the European frontline of Minimal and Conceptual art. His critical exploration of the pedestal as well as his personal base—his identity—within distinct cultural contexts is inseparable from his broader artistic and philosophical journey. In a separate room,

Untitled (1984) presents a misshapen terracotta jar, bearing traces of handcraft, resting on a makeshift pedestal assembled from scrap wood Takeoka collected on the streets of Düsseldorf. Unlike the strict minimalist syntax and Duchampian substitution that define his later works, this piece exudes a raw vitality rooted in imperfection. It offers a glimpse into Takeoka’s decision to establish himself as a sculptor in his formative

years in Germany. The exhibition title, everything for freedom, encapsulates the essence of Takeoka’s artistic practice—a conclusion of his decades-long pursuit. At the same time, it stands as his new manifesto for our present moment, where the basic structures of the world are shifting, and established values are being challenged, extending the inquiry beyond sculpture to question freedom, the fundamental nature of human beings.

(*) Ergon and parergon: These Greek terms mean “work” and “its supplementary elements,” respectively, and have been central to Western aesthetics since Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Judgment (1790). In TheTruth in Painting (1978), Jacques Derrida revisited this distinction, arguing that the frame surrounding a painting—though seemingly external—is what allows the work to appear as a work. This suggests thataesthetic value is inseparable from modes of display and institutional framing—an idea frequently referred in contemporary art since the 1980s, and offers an insightful framework for reading Takeoka’s sculptures.